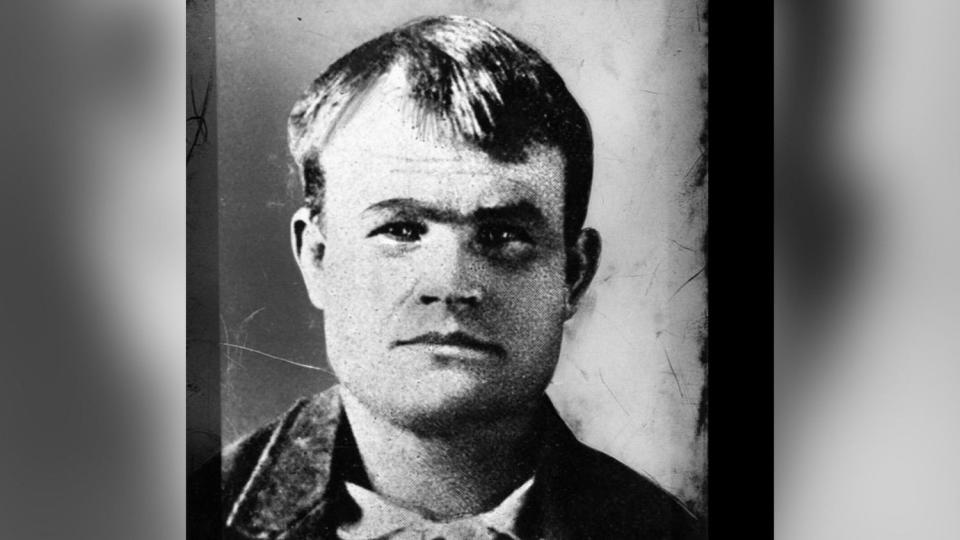

Butch Cassidy’s legacy is a bit complex.

Cassidy, whose real name was Robert LeRoy Parker, is viewed by some as a ruthless criminal who robbed trains and banks throughout the West at the turn of the 20th century. Others see his actions in a more redeeming light, as he targeted large businesses that threatened the existence of smaller ones.

What isn’t up for debate is that he was from Utah and remains one of the state’s more memorable figures even a century after his reported death.

“Whether you think he’s a villain or a Robin Hood, he’s definitely a colorful character for our state,” says Rep. Steven Lund, R-Manti.

Now, an effort to turn the childhood home of Utah’s most notorious outlaw into the state’s newest monument has cleared its first hurdle. Members of the Utah House Natural Resources, Agriculture and Environment Committee voted 11-0 Thursday to advance HCR8, a resolution to create Butch Cassidy State Monument near Circleville.

Who was Butch Cassidy?

The property, which is an attraction near the Garfield and Piute county line maintained by local officials, is where Parker grew up with his family after he was born in Beaver in 1866.

The nonprofit Utah Humanities, which compiled a short history of Butch Cassidy’s life, says family raised him there until his teenage years before they lost the farm. That’s when he met a cattle thief named Mike Cassidy and life turned.

Mike Cassidy influenced Parker to hit the road and become an outlaw, as noted by historian John Barton in Utah History Encyclopedia. It was on this journey he developed the persona for which he’s remembered.

“Parker rode the fringe between being an outlaw and a migrant cowboy,” Barton wrote. “He worked several ranches as well as one time in a butcher shop at Rock Springs, Wyoming, from which he took the name ‘Butch.’ And to not bring shame upon honest parents, he added the name Cassidy.”

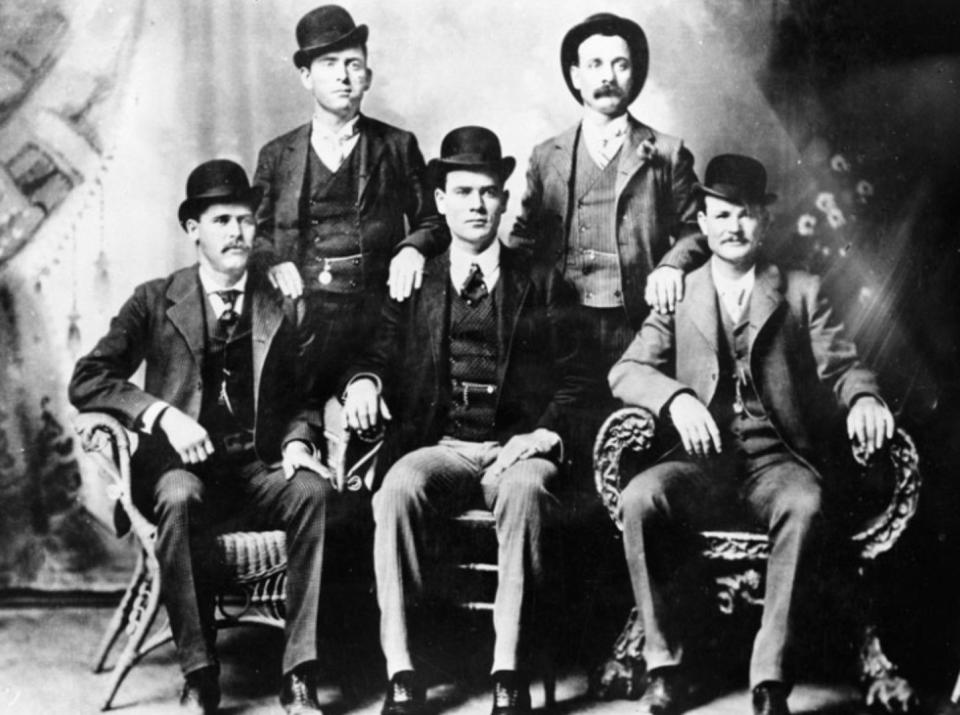

Butch Cassidy went into American folklore from there, becoming a well-known bank and train robber across the West. He would go on to form the infamous outlaw gang known as the “Wild Bunch,” which carried out some of the largest robberies in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

But some say he committed these crimes for the little guy, targeting large cattle operations that pushed smaller ones out of business, Utah Humanities noted.

“The best way to hurt them is through their pocketbook. … I steal their money just to hear them holler. Then I pass it out among those who really need it,” it quoted him as once saying.

Whatever the case may be, it made him a wanted man. The impacted railroad companies hired a detective agency to track down members of the gang, some of whom fled to South America with Butch Cassidy.

In 1908, soldiers in Bolivia finally tracked down Butch Cassidy and Harry Longabaugh, known as “The Sundance Kid,” who were reportedly killed after a shootout. But as a part of their lore, some to this day believe the two never died in that fateful shootout and lived under new identities.

Butch Cassidy’s legacy went on to be cemented in literature and cinema, including the classic 1969 Western “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford.

A new state monument

Butch Cassidy’s legacy has fueled interest in his childhood home, which was restored and is now a popular tourist destination. HCR8, sponsored by Rep. Carl Albrecht, R-Richfield, would make it a state monument operated by the Utah Division of State Parks.

Albrecht pointed out both Garfield and Piute counties approved resolutions to preserve and maintain the facility in a land lease agreement with the land’s private owner. He added the state also has a memorandum of understanding with the landowner in place, providing utilities and upkeep for the 1-acre site.

“It’ll provide more recreational, cultural, historic, scenic and economic value,” he said. “Monument status would give the area more recognition, more signage on maps, more (identification), resulting in more visitors to the area. … It would just be a great economic driver, I think, for Garfield and Piute counties.”

The motion garnered support from local leaders who attended the meeting, as well as the division. There wasn’t any pushback from committee members before they passed the measure to a full House of Representatives vote.

“This is a great use and a way to care for and be wise stewards of the history and the treasures we have here in the state,” said Rep. Kevin Stratton, R-Orem, before casting his vote in favor.

The bill must be approved by the House and Senate by March 1 before it can be signed into law.